Continuing our series in Remote Sensing, this week we are examining Magnetometry

Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) has become an invaluable tool for archaeologists, revolutionizing the way subsurface investigations are conducted. This non-invasive technology allows researchers to peer beneath the ground without disturbing a site, providing crucial insights into buried structures and artifacts. In the Mid-Atlantic region of North America, GPR has proven particularly useful, revealing hidden historical treasures and enhancing our understanding of the area’s rich cultural heritage.

GPR operates by emitting radar pulses into the ground and recording the echoes that bounce back from subsurface variations. These echoes can reveal variations in soil composition, voids, and buried objects, which are then used to create detailed maps of what lies beneath the surface. This technology is especially effective in identifying features such as foundations, walls, and even unmarked graves, making it a versatile tool in both urban and rural settings.

In the Mid-Atlantic region, which encompasses states like New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, and West Virginia, GPR has been instrumental in uncovering significant archaeological sites. This region is steeped in history, from early Native American settlements to colonial towns and Civil War battlefields. GPR has allowed archaeologists to explore these sites with a level of precision and detail that was previously unattainable.

One of the notable applications of GPR in the Mid-Atlantic is its use in urban archaeology. Cities like Philadelphia and Baltimore, with their long histories of human occupation, pose unique challenges for archaeologists due to the dense overlay of modern infrastructure. GPR surveys have successfully mapped out buried foundations of colonial-era buildings, revealing the early urban grid and providing insights into the growth and development of these cities. For instance, in Philadelphia’s historic district, GPR has helped locate the remnants of Benjamin Franklin’s house and print shop, offering a glimpse into the daily life of one of America’s founding fathers.

Another significant use of GPR in the Mid-Atlantic region is in the study of early colonial towns that have disappeared from the landscape. GPR has been employed for investigations in Jamestown and St. Mary’s City, the colonial capitals of Virginia and Maryland. In Jamestown, GPR investigations have identified boundary ditches, post holes, and buildings, revealing a detailed view of the town’s colonial layout. Investigations have even taken place within existing buildings, such as the 1906 Memorial Church, in an attempt to discern the configuration of earlier buildings that stood in the same location. In St. Mary’s City, GPR was used in concert with other remote sensing techniques to locate the 1634 St. Mary’s Fort, which had been lost to time.

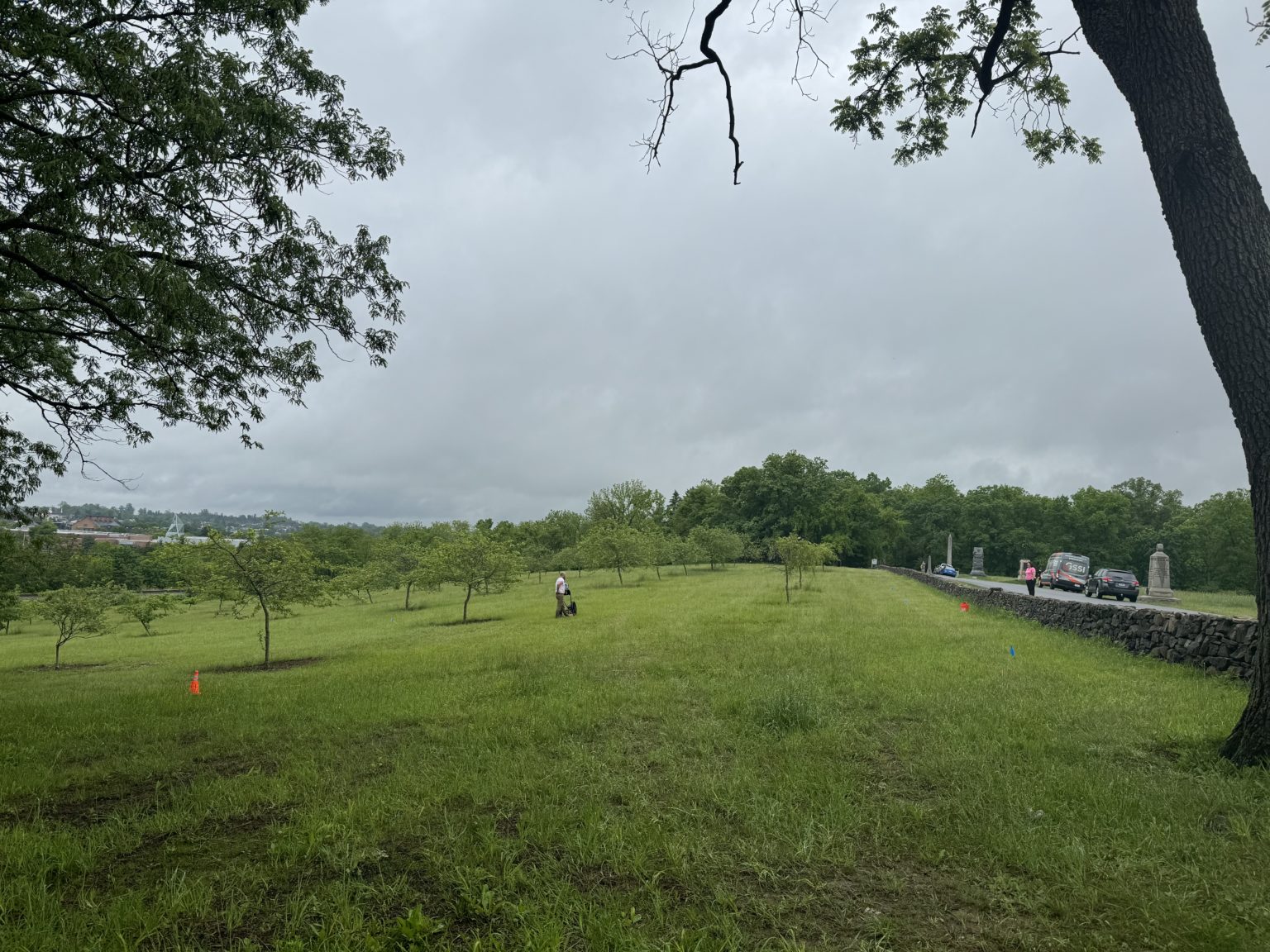

GPR’s utility in identifying subsurface features is especially valuable in the study of sites threatened by shoreline erosion. Humans have long preferred to settle near navigable waterways, many of which are now threatened by coastal erosion. GPR allows archaeologists to identify potential areas of archaeological interest and helps avoid unnecessary excavation. In this way, important information can be retrieved from threatened sites with a minimal investment of time or money. One such project recently targeted the former capital of Calvert County, known as Calverton, on Battle Creek. AAHA was privileged to partner with the Maryland Historical Trust to excavate anomalies they identified during a GPR survey and recently presented the findings of that investigation at the Mid-Atlantic Archaeological Conference.

While GPR offers many advantages, it is not without its challenges. The effectiveness of GPR can be influenced by soil conditions, with clay-rich or waterlogged soils potentially scattering radar signals and reducing image clarity. Additionally, interpreting GPR data requires a high level of expertise, as the radar echoes can sometimes produce ambiguous results. Despite these challenges, the benefits of using GPR in archaeological research far outweigh the limitations.

The collaboration between archaeologists, historians, and local communities in utilizing GPR technology highlights the importance of interdisciplinary efforts in historical preservation. As GPR technology continues to advance, its applications in archaeology will undoubtedly expand, offering even greater insights into the hidden histories beneath our feet. AAHA is proud to offer GPR services to our clients. If you think GPR might help save time and money on your project, call us today for a consultation and quote.