Welcome back to Round 2 of artifact cataloging. Last time, we talked about basic cataloging techniques and described our catalog system. Today, we’re going to focus on how we identify artifacts. How do we know what artifacts are and what type of information do we need for analysis? Unfortunately, you can’t beat experience for artifact identification abilities. Like any skill, the more you do it, the better you are. Most archaeologists learn artifact identification on the job, constantly building our knowledge as we work on different sites. The more exposure you have the easier it is to identify the small, broken, teeny-tiny bits we call artifacts.

Where does that leave the novice? Never fear! There’s a ton of resources that an aspiring Lab Director (or anyone really) can utilize to learn artifact identification. My favorite resource is the Maryland Archaeological Laboratory’s (MAC Lab) website “Diagnostic Artifacts in Maryland.” Check it out here: https://apps.jefpat.maryland.gov/diagnostic/index.htm. This website is an incredible resource that includes detailed histories (with photos) of artifacts commonly found in Maryland and the Mid-Atlantic area, both precontact and historic. They also provide a list of references with each subject if you need additional information. If I have a questionable artifact or need additional background for analysis, the MAC Lab website is always my first stop. For glass bottles, you can’t beat the Society for Historic Archaeology (SHA) website on Historic Glass Bottle Identification (https://sha.org/bottle/index.htm). This site also includes an extensive list of glass manufacturers with associated identifying marks.

Speaking of the SHA, they also have a wonderful website on twentieth century artifacts (https://sha.org/resources/20th-century-artifacts/) which helps provide some great date ranges and often a terminus post quem (or earliest possible date) for artifacts. Many museums and state historic preservation offices (SHPOs) have websites with artifact information. The Virginia Department of Historic Resources has a wonderful guide to precontact artifacts commonly found in Virginia (https://www.dhr.virginia.gov/programs/state-archaeology/). There are a plethora of published books and academic articles both on artifact identification and artifact analysis. And yes, sometimes Google is your best friend. Last, but certainly not least, other archaeologists! If you have an unknown artifact or if a type of artifact isn’t your forte, ask around. Many archaeologists tend to specialize in a particular type of artifacts. I personally love 17th and 18th century ceramics. Others focus on clothing accessories, tobacco pipes, projectile points and debitage, or horse accessories. Find an expert, make a new friend.

So now that we know where to look, what are we looking for? What type of information do we need for analysis? Typically, we’re looking for anything that would help us place the artifact in time or in society. Knowing when artifacts were manufactured helps us determine the occupation or use date of the site (to an extent, there’s always a but). If we have a site with artifacts that all date after the mid-nineteenth century, then we know the site isn’t from the seventeenth century. Twentieth-century artifacts found throughout the soil column at a site dating from the eighteenth century can indicate disturbance and a lack of integrity.

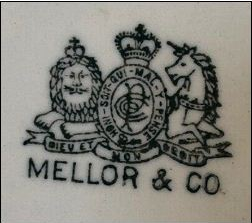

Oftentimes, ceramics and glassware will have maker’s marks, identifying marks that denote the manufacturer. These helpful little marks can tell us when the item was made, where it was made, and by what company. This information can help us better understand the site as well as the political, economic, and social context the site is within.

Concerning faunal analysis, we also look out for butchering marks, which can tell us how the animal was processed. The type of bones found can also indicate socioeconomic status. Are the site inhabitants consuming choice cuts of meat or are they buying cheaper, less desirable portions.

For 19th and 20th century artifacts, documents including receipts, bills of sale, and even old catalogs provide prices. These give us a glimpse into the socioeconomic status of the site residents. Do we have a lot of expensive, imported Chinese porcelain or do they have the knock-off refined earthenware with a Chinese-style motif? Are the utensils silver or pewter? Do the ceramic types match the proposed time period or are they earlier, indicating either hand-me-downs or heirlooming (think ‘grandmas fancy dinnerware’, you know, the ones that sit in the glass display cupboard and never get used), and which is it? These are all questions that bring the artifacts to life, that let them tell us about the site and its previous inhabitants.