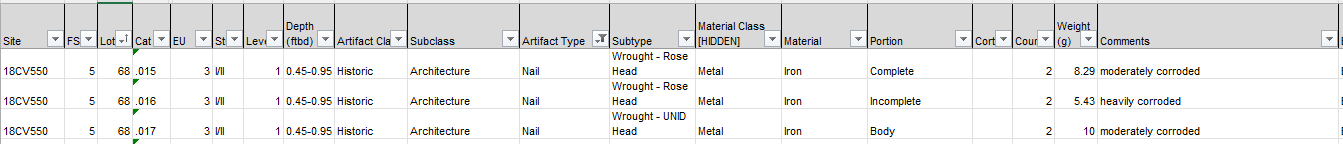

We now come to what I like to call the ‘fun’ part of Lab work: analysis! It’s like a murder mystery, but instead of a ‘whodunit’, it’s a ‘whatisit’. This is the step where we figure out what everything is, which is a critical step because if we don’t know what an artifact is, we can’t figure out what it means in a larger contaxt. So how does artifact cataloging work?

First step, we check all of the provenience information, again, just like a criminal investigation I told you it was the most important rule about lab work. It is vitally important that we maintain provenience integrity with the artifacts! Once we’re confident that everything is as it should be, we start sorting.

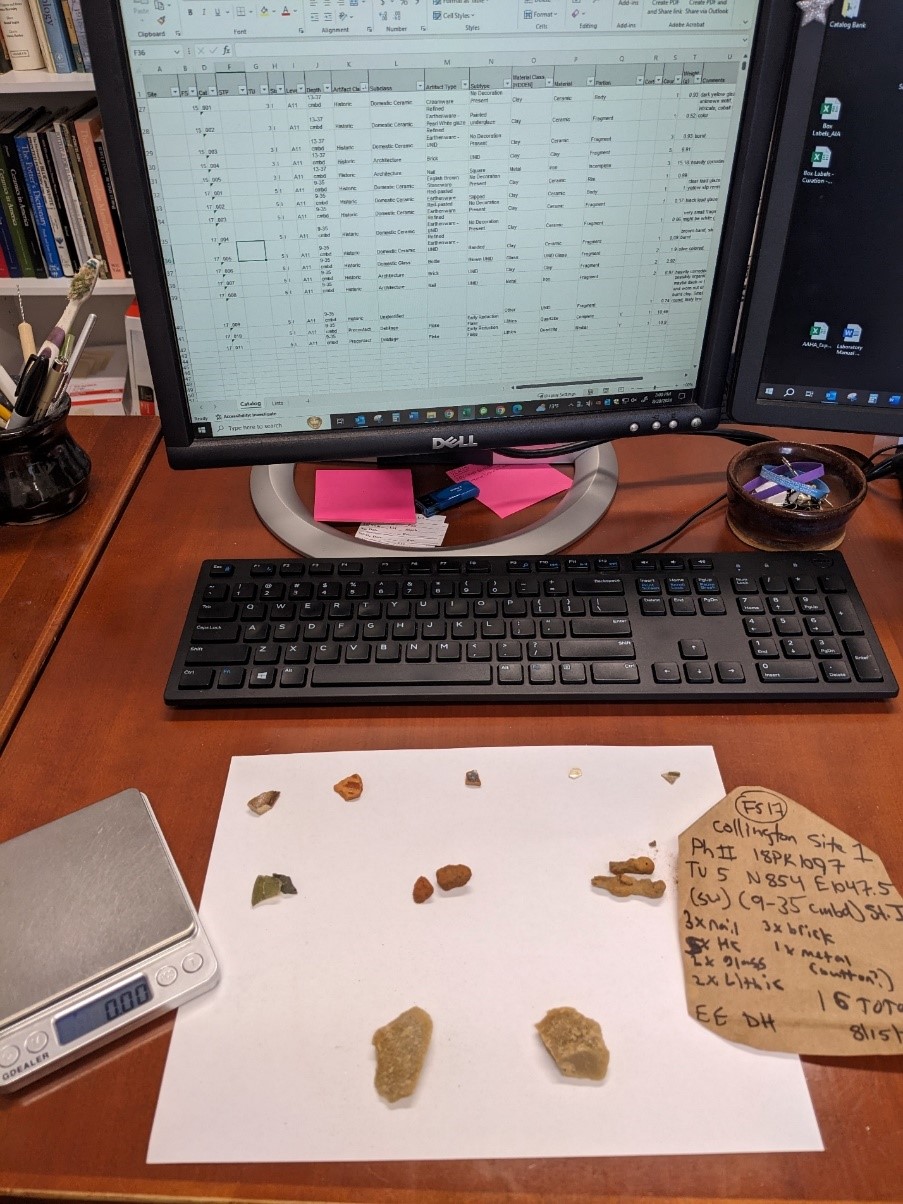

I like to sort artifacts by type first: ceramics, glass, metal, bone, etc. Once those are grouped, I get more specific. Are these rusty things nails or other metal objects? Is this ceramic Bone China or Chinese porcelain? Is this bottle or table glass? For some items, the categorizations continue. What type of decoration is present on this refined earthenware? Can I identify the motif? What type of nail is this? Is this machine-made or hand-made brick?

Our catalog system has four columns that break down the artifacts from general to specific. Artifact class is the largest: Historic, Precontact, or Organic. Subclass breaks it down into general groups. For Historic artifacts, we separate according to primary use: architectural, domestic, personal, tobacco, etc. For Precontact artifacts, it’s separated into tools, debitage, pottery, etc. Organic items include faunal, floral, and lithic items. Artifact type is specific to the artifact subclass, with artifact subtype likewise specific to artifact type. I can see your eyes crossing, stay with me, it’ll make sense.

We also include material class (glass, clay, lithic) and material (what type of glass, ceramic temper, or lithic type) and portion of the item (base, body, rim, distal end, etc). Portion is important for analysis of MNI (minimum number of individuals) or minimum vessel counts later in the analysis process (we’ll get there, be patient). Finally, we note the count and weight.

Everyone catalogs differently and every company or institution uses their own system. We use a special catalog I built (and by ‘I’, I of course mean my computer-savvy partner) using Microsoft Excel that includes fancy drop-down menus. Some companies use Microsoft Access, some use pen and paper. Our catalog includes all provenience information as well as the aforementioned columns that increase in specificity to describe the artifact.

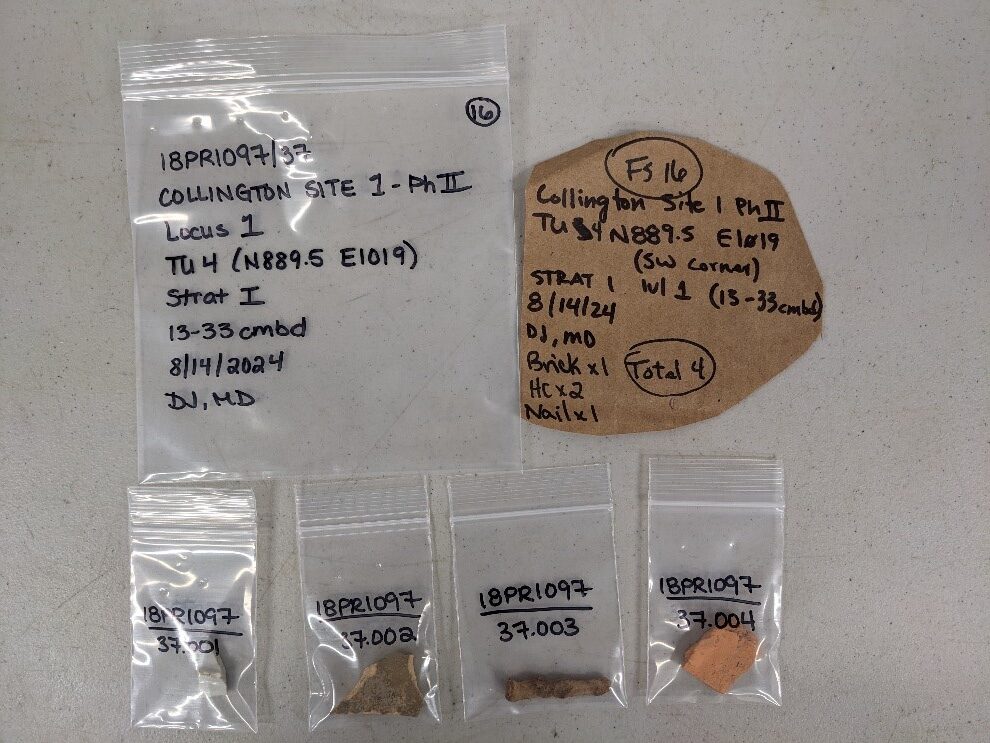

What is a typical catalog entry? Provenience information first, including the FS number, the Lot number, the Catalog number, the STP or TU, strata, and depth. The Lot number is similar to the FS number (see the previous post), but it’s assigned after the entire assemblage has been cataloged and identifies the proveniences within each site (FS numbers are project-wide and can include many sites). The Catalog number is a specific number that is assigned to each separate entry in a provenience. While the FS and Lot numbers indicate the specific provenience the artifacts are from, the Catalog number identifies the specific artifact or group of artifacts. Once we sort all that out, we start describing the artifact.

Let’s say the collection includes two hand-wrought nails. They are practically identical in every way; both are complete specimens with a rose-head with similar levels of corrosion. As all of the diagnostic information is similar, we can lump them together as one Catalog number. After I fill out my provenience information, we enter them as “Historic” “Architectural” “Nail” “Wrought – Rose Head” “Metal” “Iron” “Complete” “2” “8.29g”. After that is a comment field that lets us add anything that would not fit within the fancy drop down columns. For metal, this typically includes a note on corrosion levels. For ceramics, it could include information on the specific decorative motif (“Non-impressed, non-scalloped edge, blue painted, 1860-1890” as an example). If we had two partial nails, say just the rose-head and a bit of the nail body, we would catalog it as “Historic” “Architectural” “Nail” “Wrought – Rose Head” “Metal” “Iron” “Incomplete” “2” “5.43g”. Some labs don’t get as specific or split as many hairs as we do. To each their own.

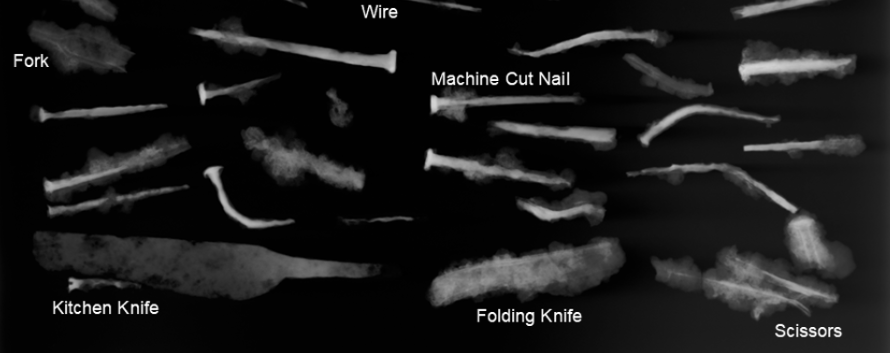

What do we do if we don’t know what an item is? Well, that’s what the “Unidentified” artifact subclass is for. If we don’t know what an item is or if it could be multiple things, artifacts get labeled as ‘unidentified’ with a full description in the comments. Typical unidentified items include very rusty iron (lovingly referred to as Cheetos); small pieces of glass that could be from a bottle, a glass, a jar, a lamp, or a window; things that are burned beyond recognition; and small or fragmentary artifacts. Just because we don’t know what they are doesn’t mean they’re not important. Sometimes additional analysis, specifically x-radiography for metals, or consultation with other material cultural experts can help with identification.

X-radiography involves x-raying (is that a word?) corroded metal. If the metal is not too degraded, this method allows us to see the artifact inside of the Cheeto and make confident identifications. We recently x-rayed a collection of rusty chunks and discovered a two-tined fork, an umbrella rib, several knives, small scissors, and were able to identify numerous nails.

We continue the process until we’ve cataloged every single item in the provenience. Then we give everything a nice, clean, archival-quality bag labeled with the site number, the Lot number, and the Catalog number plus a new overall provenience bag.

Once everything is put away, we move on to the next provenience. That’s the basics of cataloging! Stay tuned for a more in-depth analysis of artifact identification.